Over the past two decades, Parkinson’s disease has not changed as much as our understanding of it has. What once appeared predictable and uniform has gradually revealed layers of variation, uncertainty, and individuality. How AI is changing our understanding of Parkinson’s disease is not a story of replacing old knowledge, but of seeing patterns that were previously difficult to connect—across symptoms, progression, and lived experience.

How Parkinson’s was commonly understood in 2000

In 2000, Parkinson’s disease was not new, confusing, or poorly studied. There was a shared understanding—across doctors, researchers, patients, and families—of what Parkinson’s usually looked like.

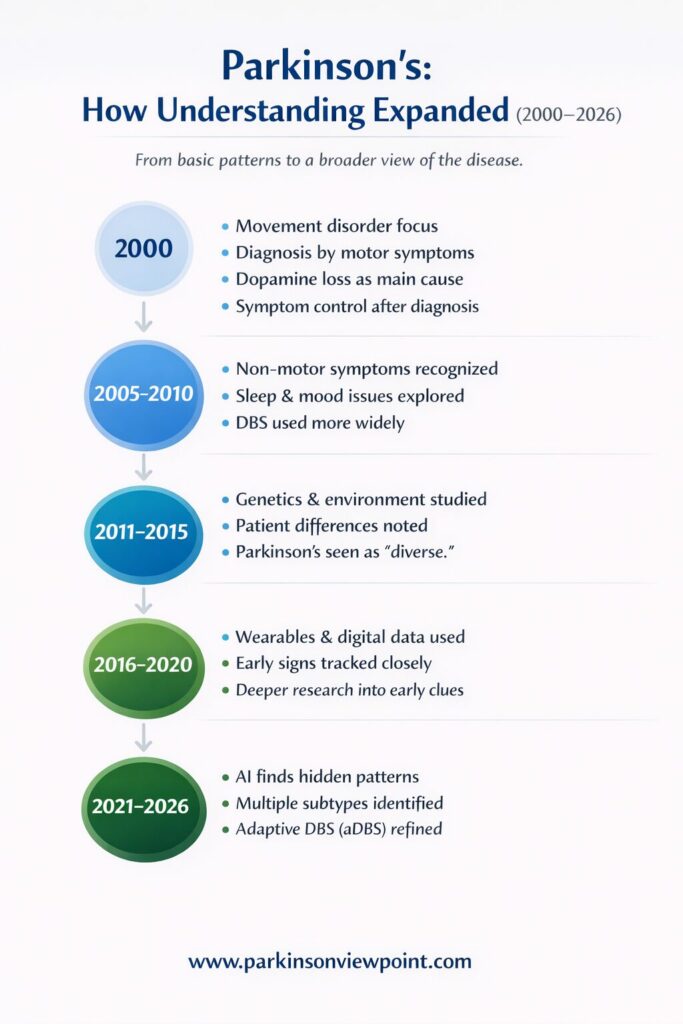

It was mainly seen as a movement condition. Tremor, stiffness, slow movement, and balance problems were the signs people expected. These symptoms were visible, measurable, and relatively consistent across many patients.

The underlying explanation also felt solid. Parkinson’s disease was linked to the loss of dopamine-producing cells in a specific part of the brain. When dopamine levels dropped, movement suffered. When dopamine was replaced with medication, movement often improved. This connection made sense and, importantly, helped people live better.

Treatment focused on managing symptoms as they appeared. Medication adjustments, physical therapy, and later-stage interventions followed a path that felt familiar and predictable. Parkinson’s disease was understood as a condition that progressed over time, usually in a steady way.

This view wasn’t narrow. It was practical. It reflected what people could clearly see, measure, and respond to with the tools available at the time.

Where that understanding started to feel incomplete

As years passed, it became harder to ignore how different Parkinson’s disease could look from one person to another.

Some people developed tremor early; others never did. Some struggled first with sleep, mood, digestion, or thinking—sometimes years before movement problems began. Two people diagnosed at the same age could have very different experiences just a few years later.

These differences were always acknowledged, but they were often treated as variations of the same disease rather than clues to something deeper. There wasn’t an easy way to connect these individual stories into a bigger picture.

Research added more pieces, but also more complexity. Non-motor symptoms gained attention. Genetic factors were identified. Environmental influences were debated. Parkinson’s disease started to look less like a single path and more like a collection of overlapping ones.

The challenge wasn’t a lack of knowledge. It was that human thinking struggles to connect large, scattered patterns across time, biology, and behavior.

What AI changed by 2026

By 2026, artificial intelligence didn’t “solve” Parkinson’s disease—but it changed how patterns were seen.

AI could analyze huge amounts of data at once: movement data from wearables, brain imaging, genetics, medication responses, sleep patterns, and long-term clinical records. These were things already being collected, just never fully connected.

What emerged was not one new theory, but many clearer ones.

Instead of treating differences between people as noise, AI helped show that these differences often follow patterns. Parkinson’s disease began to be discussed more openly as a condition with multiple subtypes, different progression speeds, and different dominant symptoms.

This didn’t replace the earlier understanding. Dopamine is still central. Medications still matter. But Parkinson’s disease came to be seen as less uniform and more personal.

AI also made prediction more cautious. Rather than promising a single expected timeline, care became more focused on probabilities and individual trends. That shift matched what many people living with Parkinson’s had felt all along.

How treatment evolved alongside this thinking

Treatment advances followed this broader view.

Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS), already known in the early 2000s, became more refined and personalized. Instead of fixed stimulation, newer systems allowed for adaptive DBS (aDBS)—where stimulation adjusts in real time based on brain signals. This reduced side effects and improved symptom control for some patients.

Medication strategies also became more flexible. Dosing schedules, delivery methods, and combinations were increasingly tailored rather than standardized.

Research expanded beyond movement. Studies focused more on sleep, cognition, mood, gut health, and early warning signs. Digital tools and home-based monitoring helped track symptoms as people actually lived, not just during clinic visits.

None of these changes came from AI alone. But AI helped support them by showing where personalization mattered most.

Related article: What is Adaptive Deep Brain Stimulation and How it Helps Parkinson’s Patients

What this means in everyday terms

For people living with Parkinson’s disease, these changes are often felt quietly.

Appointments may involve more listening and fewer rigid predictions. Symptoms that once felt “outside the box” are more easily recognized as part of the condition. Care feels less about fitting into a model and more about understanding an individual path.

There are still limits. There is still uncertainty. There is no universal cure.

But there is more room—for difference, for adjustment, and for honest conversations about what is known and what is not.

Looking back from 2026

The shift from 2000 to 2026 is not a story of being wrong and then being right.

It’s a story of seeing more.

Earlier understanding gave structure and relief at a time when clarity was needed. Newer tools expanded that structure without tearing it down. AI didn’t replace human judgment—it supported a wider view of complexity that humans alone struggled to hold.

Progress, in this sense, wasn’t about speed or disruption.

It was about learning to live with nuance.

And for a condition as personal as Parkinson’s disease, that kind of progress matters.

Disclaimer: The information shared here should not be taken as medical advice. The opinions presented here are not intended to treat any health conditions. For your specific medical problem, consult with your healthcare provider.

We’re building a simple Parkinson’s tracking app

Free during early access. Designed for daily symptom tracking without complexity.