In recent years, scientists have been looking beyond the brain to better understand what causes Parkinson’s disease. Their research has also turned to the gut, where changes in the microbiome appear to be closely linked to the condition. Studies suggest that gut bacteria may play a key role in both the development and progression of the disease. But how strong is this connection, and what does current research really say?

The brain communicates with all parts of the body to regulate essential functions. One of the most complex and important communication pathways is the one between the brain and the gut.

This gut-brain connection is powerful because it includes not only physical and chemical signals but also emotional and cognitive interactions. In fact, the gut contains the second-largest number of nerve cells in the body, after the brain.

Researchers have identified three key players in this interaction:

- The Enteric nervous system (ENS)– Often called the “second brain,” the ENS is a network of neurons in the gut wall. It helps regulate digestion and gut movement, and sends signals back to the brain.

- The vagus nerve – This is the main nerve connecting the brain and the gut. It allows signals to travel both ways, helping the brain influence gut function and the gut influence brain activity, including mood and cognition.

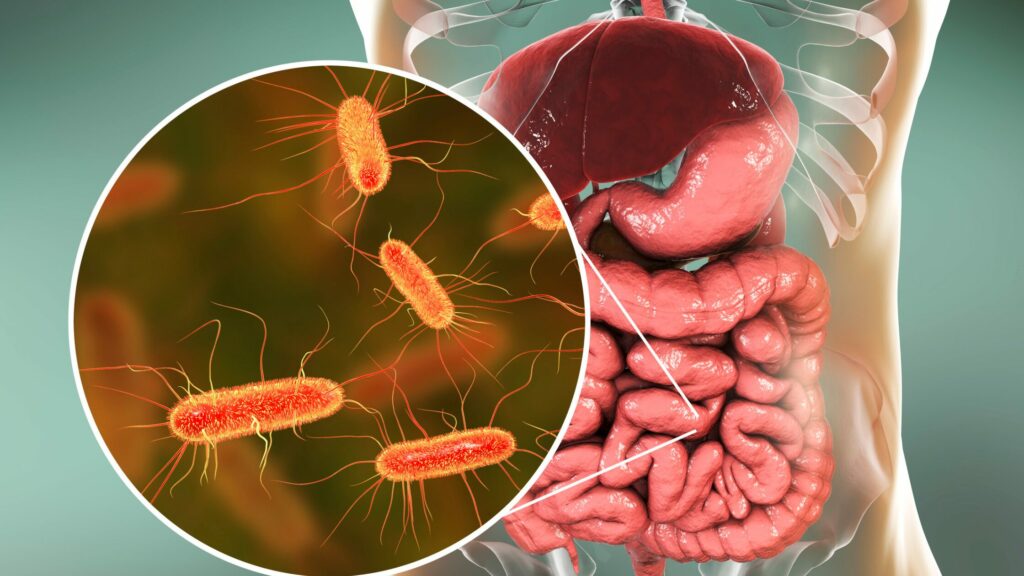

- The gut microbiome – This refers to the trillions of bacteria and microorganisms in the digestive system. These microbes help with digestion, make important chemicals like serotonin, and regulate immune responses. When the balance of these microbes shifts, it can affect brain health and contribute to neurological conditions.

Together, these systems form the gut-brain axis, a powerful line of communication that may play a role in everything from digestion to mental well-being—and even neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson’s.

What does the research say about the gut microbiome and Parkinson’s disease?

While research in this field is still emerging, growing evidence shows that the gut microbiome in people with Parkinson’s disease is different from that of healthy individuals.

A study published in the Journal of Clinical Medicine examined stool samples from Parkinson’s patients who were only treated with Levodopa, compared to healthy individuals of the same age. In total, the study included 27 PD patients and 44 controls. Using advanced genetic testing, researchers found that certain bacterial types—such as Bacteroides, Corynebacteria, Deltaproteobacteria, Butyricimonas, Robinsoniella, and Flavonifractor—were more abundant in the Parkinson’s disease group. Additionally, species like Akkermansia muciniphila, Eubacterium biforme, and Parabacteroides merdae appeared more frequently in Parkinson’s patients than in healthy controls.

Another study published in the Journal of Movement Disorders analyzed stool samples from 350 individuals, including people with different Parkinsonian syndromes. They found that newly diagnosed Parkinson’s patients had consistently lower levels of Lachnospiraceae, a group of bacteria known for maintaining gut health. This reduction was linked to more severe symptoms such as cognitive decline, balance issues, and gait problems. Meanwhile, increases in Lactobacillaceae and Christensenellaceae were also associated with worse clinical outcomes.

Researchers are now trying to explore reasons for this connection, and one major focus is a protein called alpha-synuclein (α-Syn)—a key hallmark of Parkinson’s disease. Abnormal clumps of this protein are known to build up in the brains of people with Parkinson’s disease.

Recent studies suggest these clumps may actually begin forming in the enteric nervous system—the network of nerves controlling the gut—before appearing in the brain. This may help explain why digestive symptoms like constipation often show up years before the movement symptoms of Parkinson’s disease begin. From the gut, these protein clumps may travel through the vagus nerve to the brainstem, where they can contribute to neurodegeneration.

However, scientists still don’t fully understand whether gut microbiome changes are a cause of this process, a result of the disease itself, or a side effect of medications. More research is needed to untangle this complex relationship.

Can prebiotics and probiotics help?

With the gut playing such a critical role, researchers are exploring whether improving gut health could benefit people with Parkinson’s disease.

- Prebiotics are types of fiber that feed healthy gut bacteria.

- Probiotics are live, beneficial microbes commonly found in supplements and fermented foods like yogurt.

Certain strains like Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium have been studied for their potential to ease constipation, a common symptom of Parkinson’s disease. In one study, taking these probiotics for one to three months helped improve bowel movements in Parkinson’s patients.

Another clinical trial involving 120 Parkinson’s patients showed that those who drank fermented milk containing both prebiotic fiber and probiotics experienced more regular bowel movements and relied less on laxatives compared to those who took a placebo.

While these early results are promising, it’s still unclear if probiotics help all Parkinson’s disease patients the same way. Their effects may vary depending on the individual and may work by improving gut motility, supporting mucus production, or modulating immune responses.

Conclusion

The connection between the gut and the brain is proving to be more important than previously thought, especially in the context of Parkinson’s disease. Research has shown that people with Parkinson’s disease have distinct gut microbiome profiles, and these changes may influence disease symptoms and progression. The discovery that alpha-synuclein clumps may begin in the gut strengthens this theory. While it remains uncertain whether these gut changes are a cause or consequence of Parkinson’s disease, studies suggest that supporting gut health—through probiotics, prebiotics, and possibly even diet—could offer new ways to manage symptoms.